Discover more from The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

What Eurobarometers say about the EU's legitimacy (part one)

Since 1974, the European Commission has published a twice-yearly comprehensive poll to gauge sentiment on various social and economic issues in the European Union. Today, I downloaded every one of these polls and have been busy parsing the data to get a more granular feel for what they say about the EU's democratic legitimacy and support for the EU and the euro.

Below is a summary of what I think are the most salient points from the EU's early days. I have put special emphasis on the UK because of Brexit. In the next iteration, when I look at the later days, I want to emphasize Greece as well, because of the recent crisis, and Italy, because of the present simmering crisis.

Post-Soviet collapse and pre-Maastricht was the high point

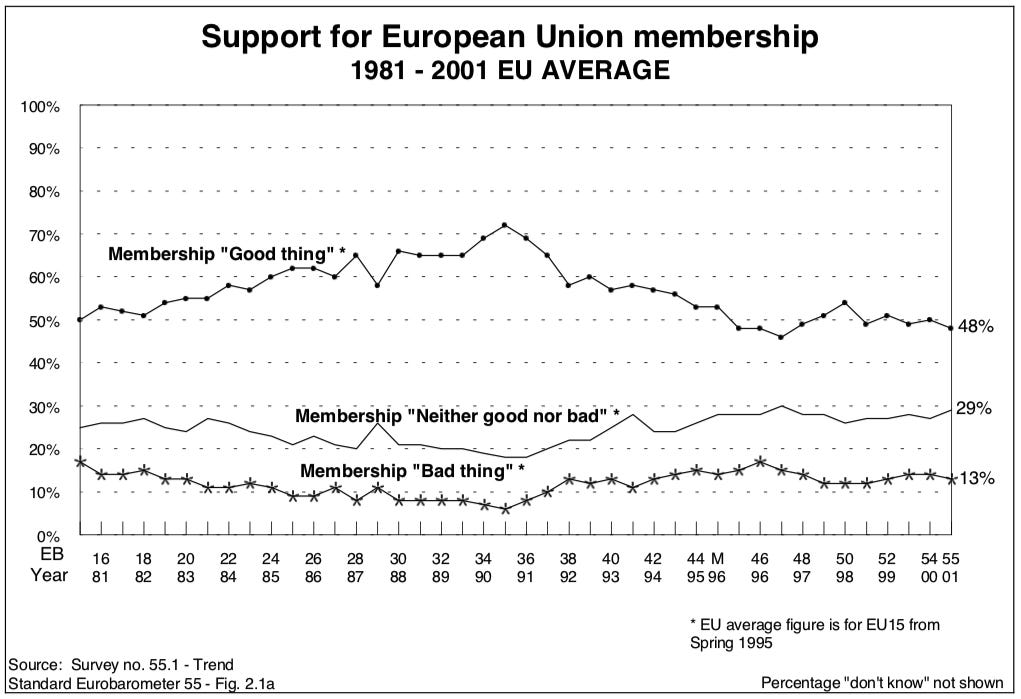

As I noted yesterday, "before the fall of the Iron Curtain, the EU’s eastern expansion, and before the euro, western Europe’s national governments and the EU itself enjoyed great legitimacy. " In fact, if you charted support for EU membership, until 1991, it was pretty much a straight line up.

But over the next decade, a nasty recession in the early 1990s, German reunification, EU enlargement, the Maastricht Treaty, and the introduction of the euro changed the EU in fundamental ways that weighed heavily on pro-EU sentiment. Support for the EU plummeted during that time period, and has never recovered since.

Here's a chart from the 55th Eurobarometer, released in October 2001, just before the introduction of the euro that marks one of two nadirs of pro-EU sentiment until the sovereign debt crisis. Support for the EU in the electorate was 71% in 1991. By 2001, it was only 48%.

The UK's relationship with the EU has always been fraught

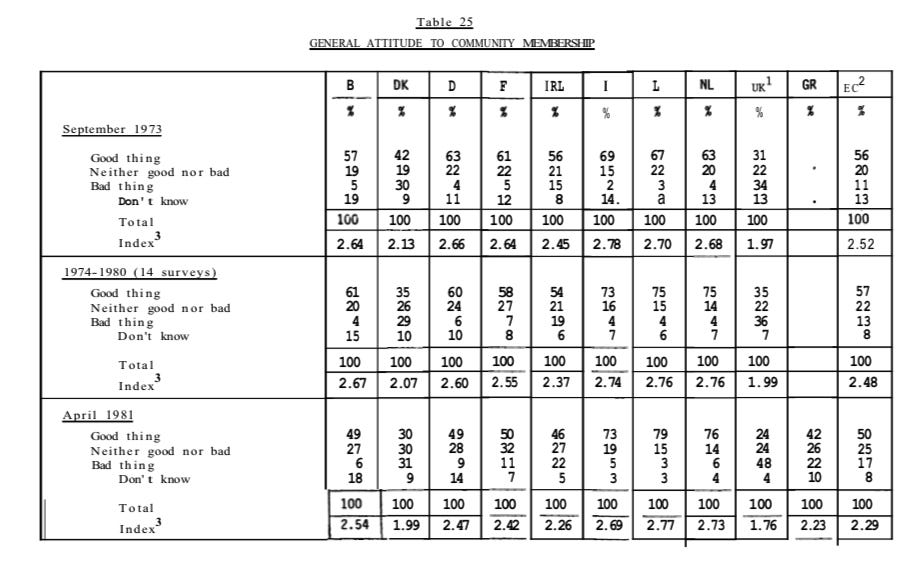

One thing I would point out is that the UK has always been a eurosceptic nation, even in the period just after its admission to the EU. Here's a chart of what each country's sentiment toward the EU looked like upon its first expansion in 1973, between 1974 and 1980, and from April 1981. This comes from the 18th Eurobarometer in December 1982.

Denmark, which joined the EU in 1973 along with Ireland and the UK, was equally eurosceptic in its early days, tying the UK with only 35% who saw the EU as a good thing. But by April 1981, only 24% of Brits saw the EU as a good thing. Fully 48% of the British population felt the EU was a bad thing.

Ireland was much more positive about EU membership right from the start. But also look at the legacy EU6 member views on the EU. They are all well above the new members.

Expansion to 12 was no problem

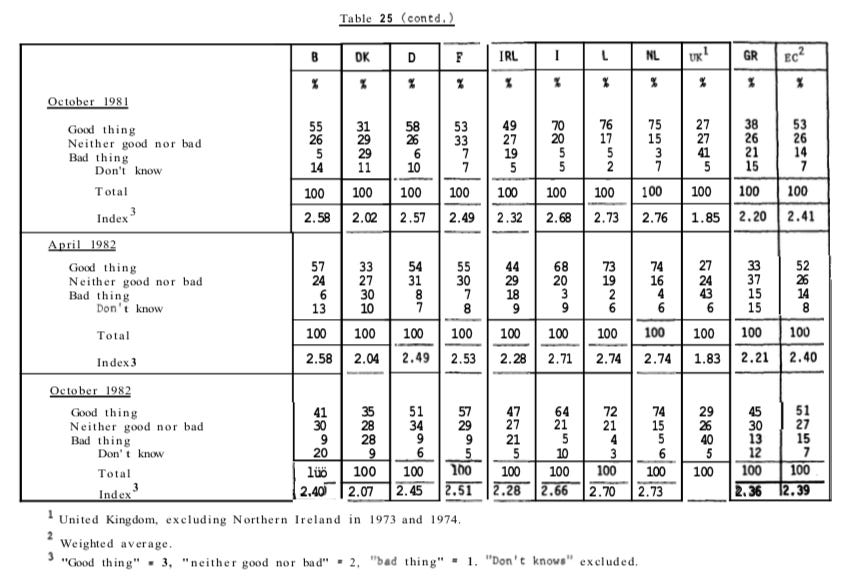

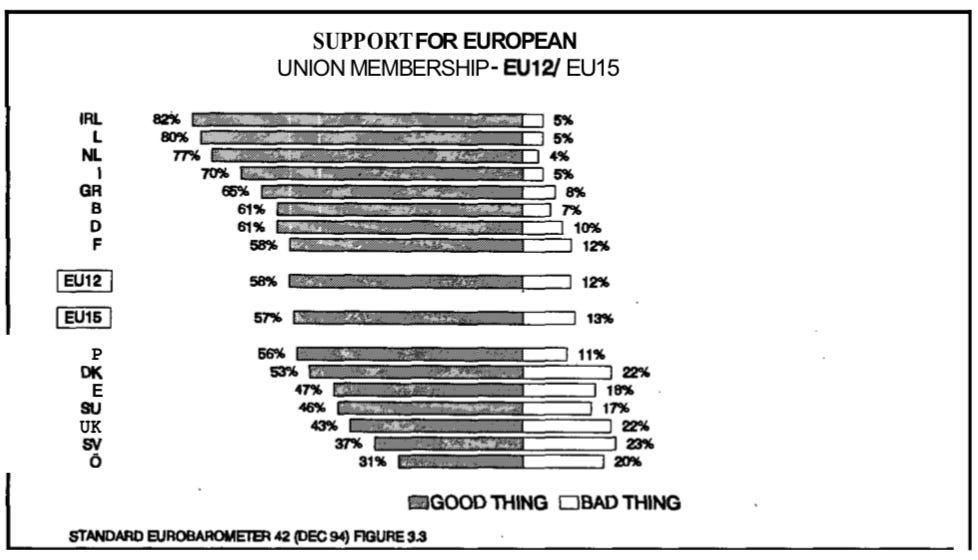

What struck me about the EU around the time that pro-EU sentiment started to fall in the 1990s was this chart below from the 42nd Eurobarometer in 1995 after Austria, Finland and Sweden had just joined.

The abbreviations you may not get are E for Spain (España), SU for Finland (Suomi), Ö for Austria (Österreich) and SV for Sweden (Sverige).

What you'll notice is that the three former dictatorships that joined the EU in the 1980s all wanted greater unification in this poll taken in December 1994. That's 81% for Greece, 77% for Spain and 76% for Portugal. So, as fraught as the EU's relationship was with the UK and Denmark after expansion in 1973, it was very good with the 1980s additions, perhaps because they received a lot of EU development funds.

But also notice that the lowest support for unification in 1994 comes from the new EU member states Austria, Finland and Sweden plus the original eurosceptics Denmark and the UK.

So, it makes sense that support for the EU continued to increase through the 1980s because the EU12 was a more cohesive unit than the EU9.

The 1990s collapse in pro-EU sentiment

So, what I have established so far is this:

The EU6 countries of France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands have always supported the EU in large numbers.

When the EU expanded to nine members in 1973, it brought in two intrinsically eurosceptic nations, the UK and Denmark and one pro-EU country, Ireland. These weren't the best of times for the EU.

But when the EU expanded to 12 members, support for the EU rose until it had 71% support amongst the EU electorate in 1991.

Afterwards, support plummeted.

The question is why.

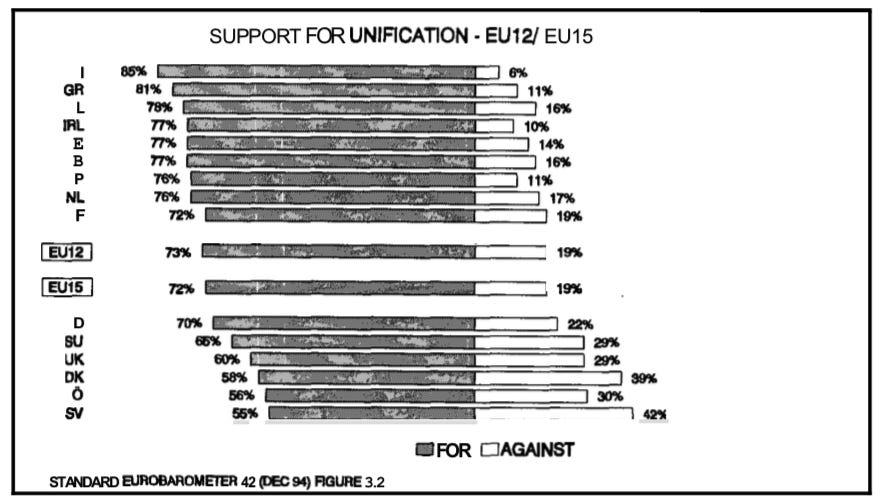

I would say the data point to a nasty recession in the early 1990s, angst around the Soviet collapse, German reunification, and the Maastricht Treaty, and EU enlargement that brought mildly eurosceptical nations into the fold. Austria was particularly eurosceptic in those early days. You can see that in the chart from 1994 below on support for EU membership.

Surprisingly, Spain at 47% and Portugal at 56% are also below the EU average in terms of support for membership. The other countries lacking support are the five I keep mentioning, all of whom were part of the EU expansion.

My conclusions

I can't help but conclude that each EU expansion has been problematic for cohesion. Two eurosceptic countries entered in 1973. Neither is on the euro. Later, three more came in the 1980s, who were only mildly eurosceptic. But because they received lots of development monies, they were a net benefit for the EU.

When the EU expanded again in 1995, once again, we had eurosceptic additions. The mitigating circumstances here are that six of the added countries were socioeconomically on par with the rest of the EU. And the other three were given a lot of transfer payments to bring them up to speed.

Moreover the pace of additions was really slow. We're talking about nine countries over a 22 year time frame. That gives you a lot of time to work the kinks out. And so, even though EU support might have dropped in the 1990s because of recession and jitters because of German reunification and the Soviets' collapse, you still had time to build cohesion.

Absent the Maastricht Treaty and the looming introduction of the euro, I tend to think the EU was on the right course. For me, the introduction of the Euro and, later, the mass introduction of 12 Eastern European members was almost too much to handle. This is especially true because Eastern Europe was socioeconomically poorer and the Schengen agreement and free movement of labor almost guaranteed a mass migration.

I would go as far as to say that, had there been no euro and a slower introduction of Eastern Europe into the EU, the EU would be the envy of the world right now.

Later, I will want to show you the data from that later period.

Subscribe to The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

A newsletter about finance, economics, markets, and technology