Discover more from The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

I had two related tweetstorms this morning whose logic I want to flesh out a bit with you. They relate to the existing macro policy world we live in and how that affects outcomes. The long and short is that the outcomes are sub-optimal and I suspect the recent Fed policy shift won't change that. More detail below

Tweetstorm One: The Phillips Curve

I am going to try to make this post mercifully brief. I am thinking of it as a pseudo launching pad for a conversation I plan to have with Ash Bennington on the Real Vision Daily Briefing today. And it continues a conversation we had around the Phillips Curve on Friday (link here).

Here's the gist:

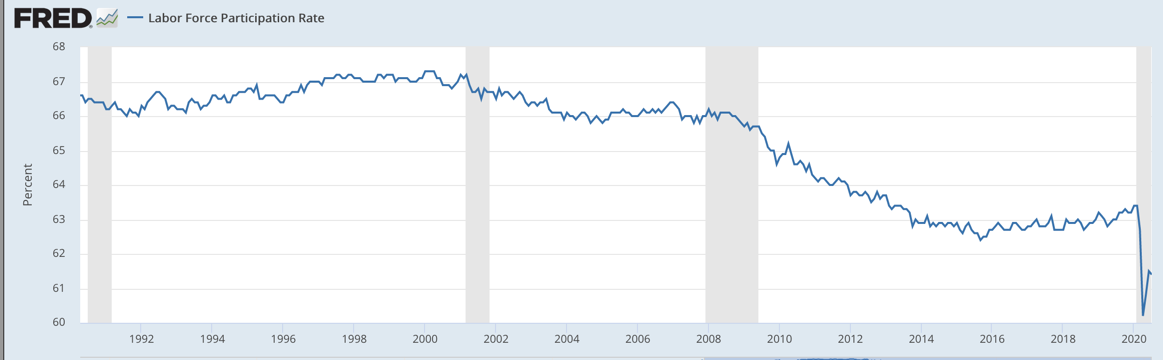

Thought bubble: when the Fed was raising rates in 2015, under the guise of inflation pre-emption, maybe it underestimated how much slack there was in the labor force. See this chart /1 pic.twitter.com/12Z4oeIAlP

— Edward Harrison (@edwardnh) August 31, 2020

Remember when we had 3.5% unemployment in the US and President Trump touted it as the greatest economy in the history of the world? Well, why was labor force participation dropping like a stone if everything was so good?

When people are dropping out of the workforce in the millions, it's hard to say you have a tight labor market.

To my mind, this chart points to massive hidden unemployment. And it's policy makers' job to let the economy run hot until that hidden unemployment is revealed and eliminated. What you want to see is increasing labor force participation. And we didn't get that. We were on our way there. Labor force participation was stable from 2014 to 2020. But then the pandemic destroyed all of that. And now we have to rebuild from a much lower base of participation.

Tweetstorm Two: Perverse Policy

Here's the thing. If labor force participation is falling, you don't have a tight labor market. The two are almost mutually exclusive. And if you don't have a tight labor market, you aren't going to get robust wage growth. Absent an exogenous cost-push shock like the Arab Oil Embargo, how does inflation get embedded and spiral upwards then? It's not like wage earners, flush with newfound wage gains are pushing up demand for goods and services, is it?

That's the world we've been living in for some two or three decades. And all along the way the Fed has been trying to preempt the inflation bogeyman.

Remember this quote:

“If we were not to withdraw accommodation, the risk would be that the economy would crash to a very, very low unemployment rate, and generate inflation,” Dudley said. “Then the risk would be that we would have to slam on the brakes and the next stop would be a recession.”

That's what Bill Dudley, then the New York Fed President, was telling people. He was basically saying that he was concerned that unemployment was getting too low.

Strange?

Well, his view was based on the economic framework from the Phillips Curve where at very low unemployment rates inflation shoots through the roof. The thinking is that there is always some frictional level of unemployment, which is why initial jobless claims never hit zero. And if you try to goose up the economy when we're at those levels, you end up bidding up demand above a restricted supply level and the result is rising prices aka inflation.

That makes sense in the abstract. But, here's where the perversity enters. First, maintaining policy to actively throw people out of work is what Bill Dudley wanted to do - and the Fed has done every business cycle. The point is to eyeball the unemployment rate - and if it gets too low, jack up the Fed Funds rate until unemployment increases and slows the economy down. The Fed thought you could get to 5.5% unemployment before its fear of inflation would cause it to hike rates. But the Fed has let unemployment drift even lower again and again without any pickup in inflation happening. They let the economy run, but they still ended up 'creating unemployment' at the end of every cycle in order to preempt inflation.

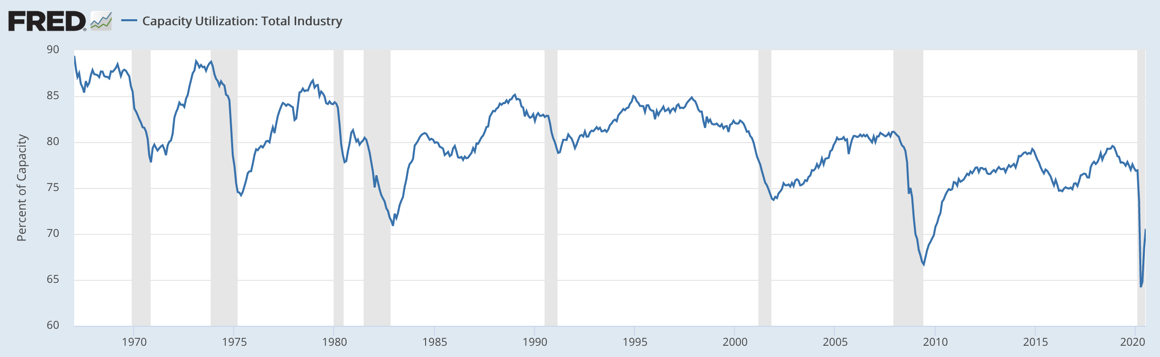

What's more is that capacity utilization has been declining every single business cycle. Look at the numbers.

Does that look like an economy on the precipice of demand outstripping supply - anytime in the last 30 years? Not to me, it doesn't. And so, Fed policy simply entrenches secular stagnation and income inequality. That was the gist of a 2017 post I used as the basis for a second tweetstorm.

My View

When the Berlin Wall fell and China entered the global supply chain, we got a massive boost to industrial capacity available to western firms. That meant global wage arbitrage keeping both wage growth and domestic capacity utilization lower. It also acted to tamp down on consumer price inflation.

The Fed, looking through this development, stuck to a Phillips Curve framework that had it preempting inflation time and again before inflation was a threat. And the result was the Fed snuffed out wage gains just as they were getting into gear, exacerbating income inequality.

Meanwhile, Hyman Minsky's two price system model was in full effect. Yes, globalization neutered inflation in the cost plus mark-up realm of goods and services. But, inflation was not neutered in the 'prospective income stream' price system for asset markets. In fact, letting the economy run, encouraged more and more speculative and Ponzi borrowing as business cycles lengthened. And so, we have seen fantastic rises in asset prices aka asset price inflation, even as consumer price inflation has remained subdued.

To my mind, this is all due to an over-reliance on monetary policy - to our asking central banks to do it all. Except when the economy enters freefall, central banks are the only game in town. And that has had very negative economic (and political) consequences.

Nothing Jay Powell said last week in his Jackson Hole comments changes this. A catch-up average inflation targeting regime does not change the over-reliance on the Fed. The continued run-up in shares and junk bonds tells you that. All investors see are more valuable prospective income streams because the Fed has issued very dovish forward guidance. They are telling us rates will be zero for the foreseeable future. So we might as well go long duration and heavy on risk assets.

This works for risk assets until it doesn't. Your guess is as good as mine as to when a re-pricing occurs. But, if we double down on the Fed as the only game in town, we won't be fixing anything. We'll simply be doubling down on a broken policy regime.

Subscribe to The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

A newsletter about finance, economics, markets, and technology

I think there was some amount of labor slack still at the end of 2019, but using the overall labor force participation rate will overstate this. The overall rate includes retirement age people. They generally have LFPRs that are 1/6 to 1/2 the rate of prime working age people (pre-retirement, non school age). Because of the wave of boomers hitting retirement age since 2010, there has been significant natural demographically driven downward pressure on the overall LFPR as a larger share of the overall population heads into age groups where the LFPRS are in the 15-40% range, vs about 80% for the prime age. There could be no change in slack, and the general progression of people into retirement years would cause that.

The prime age LFPR was depressed for quite a while, but made a fairly strong comeback over the last few years, and had essentially recovered its pre financial crisis level of about 83% by the end of 2019, and nearly regained its all time high of about 84% from about the year 1999.

That said, the problem is, the types of jobs that created this recovery in LFPR arent necessarily the types of jobs that create wage pressures. Remember, the UE rate is from the household survey, so all those freelance and uber type folks show up as employed, even though they many are scraping by and have no ability to push for higher wages. There is still a ton of competition for junk jobs, which pushes those wages toward minimum wage, with no bennies. So that is one of the many reasons the phillips curve relationship broke down. Declining union membership, general uncertainty about labor market prospects and job security, the potential for your job to be outsourced rising, and other reasons also worked against wage push inflation.