Discover more from The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

Minotaurs, Baumol's Disease, Brexit and my bone to pick with Albert Edwards

It's news Friday time. Like last week, I want to switch things up a bit and focus on the news. I am going to present a news story. And then I am going to expand on it, riffing off it and giving you 'my take' on the story. Hopefully, this will highlight some things being left unsaid.

Also, this is the perfect time to make a sales pitch! This is one of the occasional free Credit Writedowns posts I write. If you like what you read please consider subscribing to the weekday newsletter. Plus, we are running a limited promotion. So you can receive it at a 40% discount.

The Minotaurs

Being a unicorn — a private company worth a billion dollars — isn't cool. You know what's cool? Raising a billion dollars. Just yesterday, food delivery company DoorDash announced $400 million in new venture capital funding, bringing its total funding to $1.37 billion.

The big picture: Meet the minotaurs — our term for the companies that would be worth more than $1 billion even if the only thing they did was to take the cash that they have raised and put it in a checking account.

A billion-dollar valuation is easy if you've raised more than a billion dollars.

Axios has found 55 minotaurs as of early 2019. That's more than the 39 unicorns found by venture capitalist Aileen Lee when she invented the concept just over 5 years ago. (There are well over 300 unicorns today.)

The first minotaur was Alibaba, in 2005. The first American minotaur was Facebook, in 2011, followed within a month by Groupon and Zynga.

24 new minotaurs were created in 2018, a huge jump from 14 in 2017 and just 9 in 2016.

My take on this goes to what I was discussing yesterday regarding Lyft and Uber. When you get boatloads of VC money, it tilts the playing field. You can literally price below cost. And that drives out competition and potentially bankrupts competitors who don't have deep pockets.

Travis Kalanick's entry into the delivery space with CloudKitchens shows you that well-funded entrepreneurs or those with proven track records have access to boatloads of cash that make them instant players. And that money can go a long way toward creating success.

I have come to look on this period as the second Internet bubble. What's driving it is high speed mobile internet. The first bubble was a land grab like the present one. But that gold rush was fuelled by higher speed fixed line internet bandwidth. Two decades later, we have mobile Internet speeds that create a lot of opportunities for innovation. And the result is a gold rush mentality because people think network effects create a "winner takes all" situation. Clearly, there are going to be a ton of losers here. But, as with the last wave that included Google, Amazon and eBay, there are going to be very big winners to.

I think we are in the last innings of this bubble though. The shakeout will begin very soon.

LBOs

Speaking of shakeouts, here's a good news item from Reuters. The key part is excerpted below:

In a typical LBO, private equity firms juice up returns by loading up their acquisitions with debt, which is often provided by banks. But in sectors like technology, company valuations are becoming so lofty that banks will no longer finance the majority of some deals.

Without such financial engineering, the buyout firms are relying on the acquired companies’ projected high rates of growth to drive healthy returns.

This spells trouble. Basically, what's happened is that banks, sensing end of cycle dynamics, have opted out of the last stage of private equity debt financing because the multiples are too high. PE companies, flush with cash, have been forced to deploy more of that money without as much leverage in order to make the deals work.

On the one hand, less leverage is good. On the other hand, the pullback by the banks tells you a shakeout is coming down the pike. When that shakeout happens, it will be clear that the multiples have gone too high. But rather than seeing defaults because of excessive debt, we may see these recent deals simply show lower returns.

GDPNow

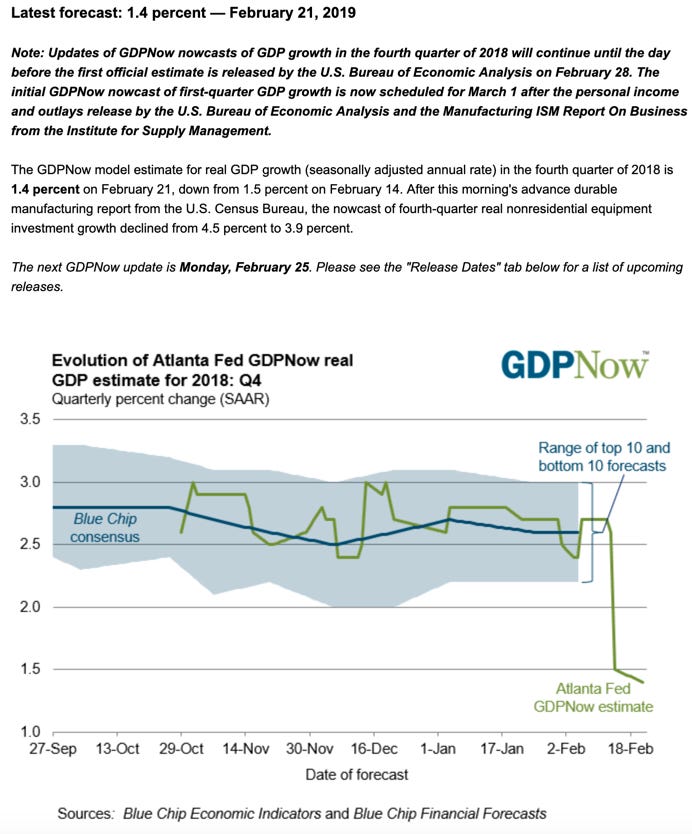

The reason for the shakeout is not just that the credit cycle is turning. It's that it may be turning just enough to send real economic growth tumbling. Look at the GDPNow numbers.

We should already know what Q4 GDP growth looks like. But the shutdown deprived us of that data. In the meantime, the data now coming out for late Q4 2018 are so ugly that nowcasts like GDPNow are being revised down quite aggressively. Before the retail sales number came out the Atlanta Fed's nowcast was in the 2.7% range. Now, it's at 1.4% real growth.

I am sceptical about the retail sales number, to be honest. So, a nowcast based off of that number is going to be too low in my view. Nevertheless, it highlights the downside risks we are seeing now, both in the credit cycle and the real economy's business cycle. Even if Q4 turns out to be more of the 2% growth variety, that's a marked downshift from growth well over 3%. It's also well below the targets set by the Trump Administration. And we can expect Q1 to be even weaker.

I have a bone to pick with Albert Edwards

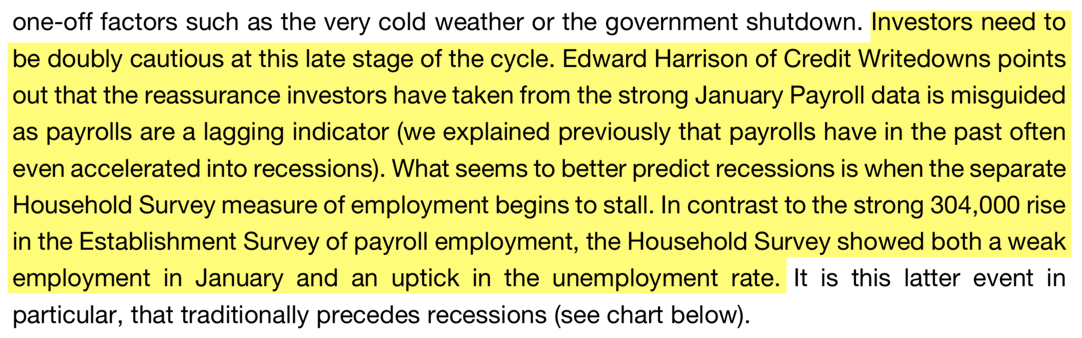

Why should we expect it to be weaker? The data

I told you two weeks ago that jobless claims are now flashing red too. At the time, the saving grace was that year-over-year numbers were still showing decreasing claims. Last week that changed. And this week, the numbers continue to show weakness relative to year-ago numbers. The 4-week average is now 235,750 for initial jobless claims. A year ago it was lower at 227,250.

And this has nothing to do with seasonality because the same uptick is evident in the non seasonally-adjusted averages too. This is why I look at year-over year numbers, by the way - because you can take out the impact of seasonality. How much of this is distortion from the shutdown? I don't know. But we will find out in due course. My view here is that if this trend remains intact for more than a few weeks, we should expect Q1 2019 GDP growth numbers to be materially lower than Q2 or Q3 2018. And given what we're seeing regarding Q4, it shows a trend of aggressively decelerating growth in the US that is quite alarming.

As I've mentioned previously, these same trends hold for unemployment rates too; they are coincident or leading indicators when looked at on a rate of change basis. Rising unemployment rates and jobless claims coincide or precede recessions.

My friend Albert Edwards picked up on my discussion of this in his missive yesterday, giving me a shout out.

I was very pleased with that until another friend of mine pointed out that Albert finished his analysis with some figures from David Rosenberg, calling him "the excellent David Rosenberg".

Of course, my friend Scott sent me that email to needle me. And he succeeded. Albert, what do I have to do to win "the excellent Edward Harrison" label? I am going to have to up my game, folks.

Negative rates

Speaking of Albert, do you remember my writing this from two weeks ago?:

Let me start this with a shout-out to SocGen strategist Albert Edwards. On the back of a San Francisco Fed piece, he predicted the US would be forced to move to a negative interest rate policy (NIRP) regime when the next downturn hits. And I thought he was onto something.

The Fed has a very limited arsenal right now, frankly. And it has paused already. It may be done. When the next downturn hits, what does it do then?...

Pedro da Costa has cottoned onto this too, now. Here's an excerpt from his excellent analysis over at Forbes from yesterday (Albert did you see that 'excellent' I added!):

With benchmark borrowing costs still in a 2.25% to 2.5% range after several increases starting in December 2015, policymakers worry about their limited ability to reduce interest rates in response to a future economic shock that causes a spike in unemployment.

The Fed has historically slashed rates by as much as four or five full percentage points in response to recession. It will clearly lack the room to do so the next time around.

[...]

Fed officials were reluctant to follow the lead of countries like Japan and Switzerland, which implemented negative rates—effectively taxes on bank deposits during the last downturn. The reasons were varied, but centered around potential trouble for money market funds, which are more predominant in the US financial system and could find it hard to break even if rates went negative.

But a recent San Francisco Fed Letter suggests some US central bankers are warming to the idea.

It finds negative rates could have made the Great Recession of 2007-2009 less shallow and less lengthy, potentially saving millions of jobs in the process.

That's exactly what Albert was saying. And I think Pedro is being conservative here. The analysis I have done says the average cut in policy rates in recessions since Volcker has been over 6%. With 2.5% of runway, the Fed will be in big trouble.

Inflation

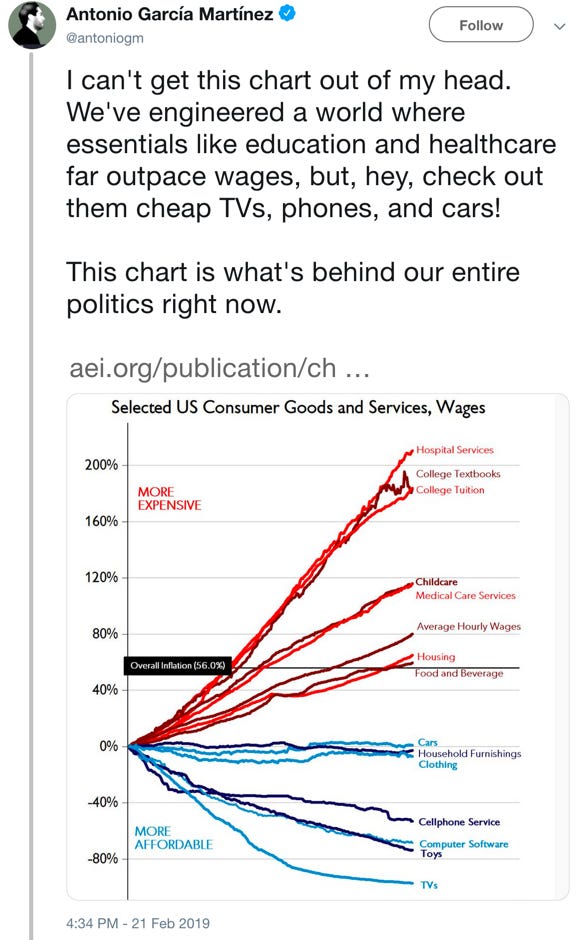

This is a chart in the news rather than a post. The same friend who needled me about Albert sent me a link to this tweet.

Notice what's going up and what's not here. It's like saying there's inflation in the things we need and deflation in the things we don't. I wrote this up about two years ago from the perspective of Baumol's disease.

The basics are simple: rising wages across the economy put huge pressure on labor intensive economic sectors because they cannot use productivity gains to reduce the impact of labour costs on their income statement. The result is a cost pass-through to consumers in those sectors of the economy. We’re talking about essential economic sectors like healthcare and education. This is something Baumol sketched out back in the 1960s. And he has proved right in the intervening 50-odd years on how these sectors have become relatively more expensive.

[...]

Yes, the cost of other goods and services will go down, making healthcare still affordable for the mean American household. But in the real world – one beset by rising wealth and income inequality, it is the median that counts. There are a lot of households that are going to be squeezed by healthcare costs – so much so that, unless they run up a lot of debt, their spending will be crimped.

Why this matters. Baumol’s disease in a world of inequality is a recipe for lower growth. And that’s a world in which political radicalization increases. Unless we solve this problem, we are due for some serious economic and political turbulence as healthcare becomes less and less affordable for a large segment of our population.

So, I agree with the AEI tweet's conclusion. But I come at it from a different angle.

Brexit

Speaking of rising discontent, look at Brexit and the splintering of parties. Jeremy Warner at the Telegraph had this to say on the subject of The Independent Group:

For the moment, the new centrists are on a high of righteous self belief. It would only require the triumphant return of the Prince across the water, David Miliband, to complete the picture of supposed manifest destiny. But in their euphoria, they have fallen prey to a kind of delusion. They claim to reject the extremes of Right and Left, but haven’t yet twigged that actually it is they themselves who represent much of what people have been rebelling against.

[...]

The defining characteristic of that consensually-driven form of government was that it was meant to be sensible, pragmatic, evidence based, and rooted in hard economic realities. In Blair’s day, it offered “excellence for all”, an “end to boom and bust”, and other such drivel.

But just look at what it managed to deliver. In Europe, it gave us the grimly destructive euro, and in America and the UK, first a quite possibly illegal war in Iraq and then the financial crisis. The economic complacency that led up to the Lehman bust found its mirror image in the political conceit of the time, consensus triumphing over ideology. They were two halves of the same coin, the one living in a symbiotic, back scratching relationship with the other.

[...]

They have no more credible an answer to the great challenges of our times than the extremes they complain of. That we are in an almighty hole, that our politics are broken and that we are struggling to find a way forward, is not in doubt. Regrettably, resuscitating a corpse that in truth died with the financial crisis is scarcely likely to be the solution.

I agree with all of that. Macron and Merkel are the last important representatives of centrism on the world stage. Soon they will be gone. And when they leave, they will not be replaced by centrists.

As for the actual day-to-day politics of Brexit, I continue to believe we are likely to see a delay, because opposition in parliament to a no-deal outcome is high. But that is not because of any political move toward the center. It's simply a recognition that a no-deal Brexit could be the shock that pushes us all over the edge.

Unfortunately, Ive run out of time. But I hope you've enjoyed this post. Have a great weekend.

Subscribe to The Credit Writedowns Newsletter

A newsletter about finance, economics, markets, and technology